Recently, I have been playing with UEFI secure boot and custom modules. I am one of the lucky people to own one of the discontinued Odroid H2+ models, a small board with decent computing capabilities.

The Odroid features an x86 CPU, so there are no ARM weirdnesses to worry about. However, the default BIOS setting of this board seems to be UEFI Secure Boot off. But what even is Secure Boot?

Secure Boot is a method to prevent Rootkits and other malicious software to execute code during boot. While the system is booting, it is generally less protected. If the operating system has not yet loaded, any protection provided by the OS is not yet working. The earlier something runs in the boot process, the more power it has: It can control all execution after itself.

While Secure Boot also has weaknesses and it sometimes debated, it is supposed to alleviate some of these concerns. UEFI Secure Boot ensures that all code part of the boot sequence is authenticated and has not been tampered with.

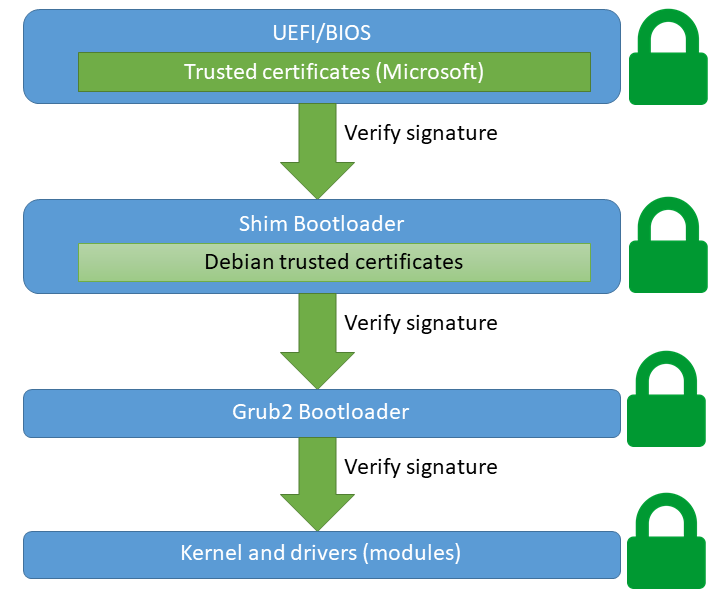

This graphic means that everything involved during the boot processes must be signed by a trusted certificate. We’re assuming Debian here. By default, most mainboards (UEFI’s) only ship Microsoft’s Root UEFI certificate. Most first-party bootloaders will therefore be signed with Microsoft’s key, to be compatible everywhere.

However, non-Microsoft projects use their own infrastructures and don’t want/can’t have every update signed by Microsoft. Instead, they use their own certificates. My Debian 11 uses two certificates for this, including Debian Secure Boot Signer 2021 and Debian Secure Boot CA. These certificates ensure that non-Microsoft signed code can load. A so-called “shim” bootloader is signed by Microsoft and will load the Debian-specific code and certificates. Therefore only the shim needs to be signed by Microsoft.

Also, in case this was not clear: UEFI Secure Boot requires an UEFI boot. If your OS was installed via the legacy BIOS system (you’re booting legacy), you can’t use UEFI features such as Secure Boot. You will need to migrate to UEFI first, which often involves a difficult bootloader swap or just reinstalling the entire system with UEFI enabled. Modern systems usually come with UEFI on by default.

My Odroid H2+ has two Realtek 8125B 2.5 Gbit network cards onboard. These are damn nice things, multi Gigabit for a cheap price. However, as with all new hardware on Linux, one question is always there: “Does it work with my Linux kernel?”.

If you run an operating system with Linux kernel 5.9 or higher (Debian 11, Ubuntu 20.04+ with HWE kernel…), the answer is yes: It will work out of the box, as the R8169 module/driver shipped with the kernel supports RTL8125B since 5.9.

However, my tests indicated that while the network cards indeed work, throughput wasn’t great: I was getting barely 2 Gigabit/s in an iperf3 test, nothing close to the 2.5 Gbit/s promised by the specification. So I had a look around whether there are better drivers. Indeed it looks like there is:

Realtek indeed seems to ship its own first party driver – it’s even open source and GPL licensed, but not included in the official Linux kernel source tree. Still, I tried out this project, which builds a nice DKMS kernel module out of the Realtek driver. DKMS is “Dynamic Kernel Module Support”, a framework to generate and load kernel modules easily. It takes care of things like recompiling your modules when you upgrade your kernel or switch configurations.

After installing the DKMS module, we had the new Realtek driver (module) available. However, even after a reboot it wasn’t active: My kernel seemed to prefer its inbuild R8169 module, so I had to explicitly block that (using the method described in the readme). After this, my kernel was forced to load my new Realtek R8125B module.

That was a great success! The new module achieved a steady 2.5 Gbit/s throughput with various HTTP/iperf speedtests, just like the specification promised.

Then I enabled UEFI secure boot. And all of my network connections broke 😞. I realized the issue: My DKMS module was not UEFI signed, so the Secure Process would refuse to load it. The OS would still boot, but without the module. Because I had disabled the R8169 module, no network card driver was available.

Obviously I could just have disabled secure boot again, but that would be no fun, would it? Instead, I wanted to get Secure Boot running and keep the R8125B Realtek module. After a bit of googling, it appears that the preferred way of doing this is by employing a so-called Machine-Owner Key (MOK). That is essentially just a certificate + private key that you generate, own, and control. You add that certificate to your UEFI certificate storage, where it will be retrieved by the shim loader. It will then be available to validate kernel modules. Note that this key can by default validate everything, including your own bootloaders, kernels etc. It is possible to limit the MOK to be only valid for kernel module validation (this involves setting a custom OID on the certificate), but doing this is out of scope for this blog post. Our certificate can be used for any purpose, including loading of DKMS modules – if you have signed them with your key.

There are various tutorials out there for various distributions and versions thereof. Here’s what I did – I hope that this is the recommended way, but I’m not entirely sure.

IMPORTANT: If you’re doing this on Debian (like I did), please read Debian’s notes about Secure Boot. It includes compatibility warnings and some pitfalls, such as validation issues in certain cases.

First of all, we need to generate our MOK, meaning a certificate and key. UEFI uses standard X.509 certificates, so if you’re familiar with them this is nothing new:

# Note: This command, and pretty much everything

# else needs to run as root.

openssl req -new -x509 \

-newkey rsa:2048 \

-keyout /root/uefi-secure-boot-mok.key \

-outform DER \

-out /root/uefi-secure-boot-mok.der \

-nodes -days 36500 \

-subj "/CN=Odroid DKMS Signing MOK UEFI Secure Boot"

For those unfamiliar with X.509/OpenSSL, here’s a quick overview: This command generates new RSA private key and corresponding self-signed certificate. We store the key in /root/uefi-secure-boot-mok.key (only accessible as root, important so that no malicious non-root party can use our key) and the certificate in /root/uefi-secure-boot-mok.der. The certificate is valid for 100 years, which isn’t ideal for security, but I am lazy. If you’re paranoid, you might want to lessen the lifetime and rotate your MOK from time to time. You might also want to consider using something else than RSA 2048 keys, but consider that your UEFI loading process must support it. The Subject Common Name (CN) is arbitrary, choose whatever your like.

Next, we need to import that certificate into our UEFI firmware store, where it can be loaded by the shim. Debian and other distributions (like Ubuntu) provide excellent tooling support for this: The Mokutils and MokManager. Basically, we just run this command (as root):

mokutil --import /root/uefi-secure-boot-mok.der

When you run this command, it will ask you for a password. Choose any password, but consider the following:

- You will need to type in this password in a short time again. You will only need this password once, it’s a one-time use thing.

- You will type in this password in an environment that will likely not use your native keyboard layout, but a default QWERTY one. If possible, choose passwords that you can type even on foreign keyboard layouts.

This does not actually do any real import. What this does instead is it marks this certificate as pending for inclusion for the MokManager. The MokManager is a EFI binary (i.e. a bootable system) included with UEFI-enabled Debian/Ubuntu systems. This is the actual workhorse that will do the import.

We now reboot the system, just use the reboot command or whatever you prefer. Ensure that you have access to a display and keyboard physically connected to your device. After the reboot, you will be presented by the MokManager waiting for you. You probably need to press some key to confirm, otherwise it will just revert to a standard boot. Once you are in the MokManager, just navigate through the options it presents to you. Press “Enroll MOK”, “continue”, “yes”, then enter the password we just setup. The MokManager may use a different keyboard layout! Once that is done and your password is accepted, select OK and wait for the reboot. Your MOK is now installed!

With the MOK installed, the final piece is to sign our DKMS modules with our key. This is very easy with Debian 11 installations, as there’s a ready made helper for this. We just need to edit two files:

Edit /etc/dkms/framework.conf and remove the comment regarding sign_tool:

## Script to sign modules during build, script is called with kernel version

## and module name

sign_tool="/etc/dkms/sign_helper.sh"

We also need to tweak the sign tool slightly, edit this file too and adjust the paths of the certificate and key:

/etc/dkms/sign_helper.sh

#!/bin/sh

/lib/modules/"$1"/build/scripts/sign-file sha512 /root/uefi-secure-boot-mok.key /root/uefi-secure-boot-mok.der "$2"

Just use the same filenames and path’s you’ve used while generating the cert + key above. This tutorial uses the same names and paths in all examples for consistency.

Now, we’ve almost done it! DKMS will now sign all modules while they’re build/installed, no additional configuration necessary!

In case you have already installed (unsigned) DKMS modules, we will need to re-build them to ensure they get signed. For my realtek module this involves the following (root again):

dpkg-reconfigure realtek-r8125-dkms

The exact command here varies depending on what modules you have, but the general idea is to call dpkg-reconfigure for each DKMS module you have. DKMS modules itself should be managed by Debian’s “.deb” package system, which is is called dpkg. The Realtek DKMS module is installed by a .deb package called realtek-r8125-dkms, hence the above command will re-install this DKMS module.

Finally, reboot a last time and your modules are now loaded – with UEFI secure boot on!